(a pictorial exhibition 1833-1933)

From Kabul to Kandahar is the title of a pictorial exhibition at London’s Royal Geographical Society which can be seen from 16th April to 1st June. The pictures are photographs or engravings and they were all made by British visitors or residents in Afghanistan in the years 1833-1933.

Some years are very well represented. The first of these is 1842, the year in which an entire British army had been slaughtered on the road back to India from Kabul and a new army had been sent in again almost immediately. With it went an artist called James Atkinson who gave the British one of their earliest images of fierce mountain tribesmen, Beloochees in the Bolan Pass.

This was the period known as the First Afghan War. However not all of Atkinson’s sketches were of fighters and fighting. Like many British visitors to Afghanistan, he was “astonished by the luxurious appearance of the fruit shops with their melons, grapes, pears, apples, plums and peaches”.

Here he shows the main street in the bazaar at Kabul in the fruit season. Look out for the very un-Afghan boy in the foreground with his British-style trousers.

By 1895 the British had changed their attitude to fruit. A British surgeon working at that time in the Afghan royal court wrote that “fresh fruit, as soon as it is ripe and even before, is eaten in large quantities, far more than is good for the health of the people”. The belief that too much fruit could be bad for you lasted until very recently in Britain.

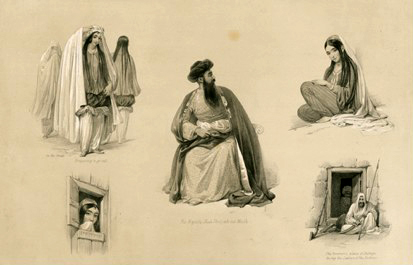

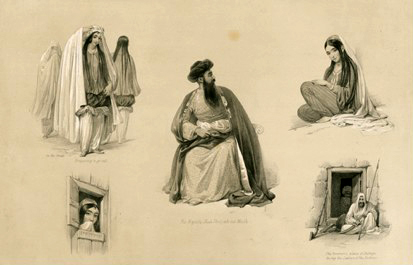

James Atkinson was one of the few illustrators to capture images of women. Did he get the women to pose for him? Or did he use his imagination and his recollections of the Thousand and One Nights?

The British and their army had all left Afghanistan by the end of 1842. Their attempt to put a king of their choosing on the Afghan throne had failed. What the British wanted was an Afghanistan which was friendly to them and rather less friendly to the Russians. The British ruled India and were extending the borders of their empire into Sind and the Punjab – right up to the border with Afghanistan. The Russian empire was advancing into what was then called Turkestan – right up to Afghanistan’s northern border. So Afghanistan became a buffer between the two empires. Relations between Britain and Russia were bad.

At the end of the 1870s the British were very worried: they felt that Afghanistan was becoming too friendly to the Russians and, once again, they sent an army to Kabul. This was the Second Afghan War. This time they brought cameras, one of which was used to great effect by Benjamin Simpson, a senior medical doctor. Several photographs by him are dated 1881, yet the British had once again withdrawn from Afghanistan in the spring of that year. Simpson caught that Afghan spring beautifully just outside Kandahar.

Even in black and white you can still see the almond trees flowering along the borders of the fields. 126 years later this is still one of the most beautiful sights in Afghanistan. You can see it outside Kabul and elsewhere, Simpson saw it outside Kandahar. Simpson had a fine eye for composition and his photographs were published in India in a “Catalogue of 76 Views”.

Simpson saw other things too, some no doubt of official professional interest, like Artillery Square in Kandahar.

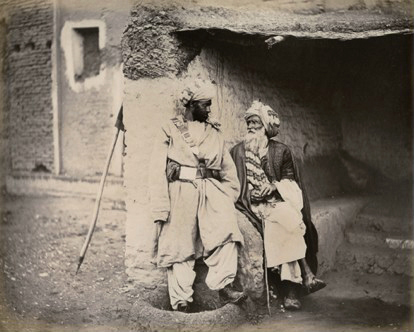

Horse-sellers without horses. But the old man in Simpson’s picture is probably not very different from the most famous Afghan horse-dealer of them all, Mahbub Ali from Kabul, who spied for the British (and against the Russians) in Kipling’s great novel Kim which was published in 1901, just twenty years after Simpson took this picture.

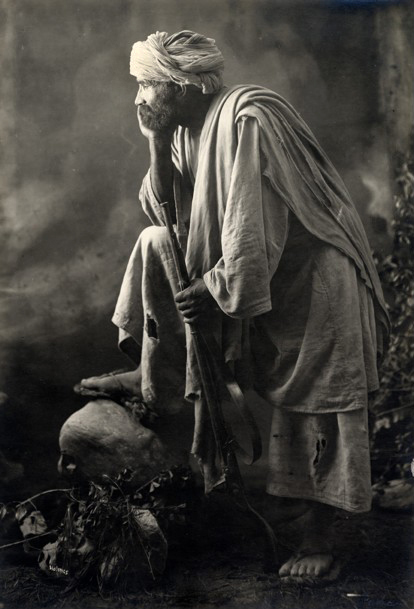

After the Second Afghan War the British Army skirmished with the tribesmen along what was called the North West Frontier. Many myths grew up about the Pashtun or Pathan tribesmen. In the popular British imagination they were no longer regarded just as cut-throats and bandits (remember James Atkinson’s picture of the Baloochee tribesmen from 1842). They were portrayed as serious, handsome and even thoughtful fighters, as in this striking studio portrait dated 1919-20 by a photographer called R B Holmes.

If Abraham had had a rifle, he would no doubt have looked like this.

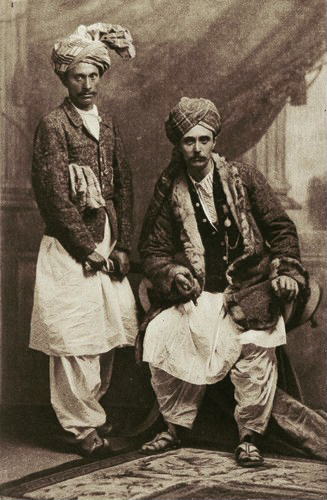

Dr Gray must have been a character. Underneath his Afghan clothes he has a European waist-coat with a medal and a watch-chain, and in his right hand he has a cigar. Maybe the picture was just a joke to amuse the family back home?

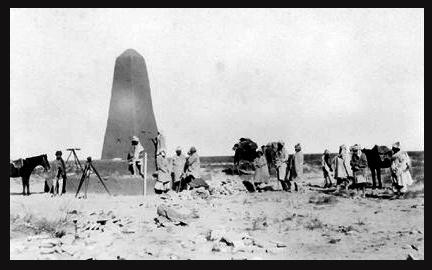

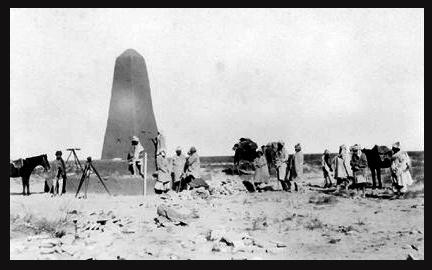

The British tried to delineate the frontier between India and Afghanistan. Teams of surveyors marked out the results on the ground, and photographers like TRJ Ward in 1921 recorded the team efforts at Boundary Pillar No.70.

You can see the surveying equipment, the pack-horses and the camels. There’s even a European lady standing in front of the two camels. She’s just to the right of the centre of the picture. The British Empire was clearly growing soft by 1921.

The last pictures in the Royal Geographical Society’s exhibition were taken in Herat. One continues the military theme, though we are not told who the photographer was or why the picture was taken. It shows half-track army vehicles with trailers in front of the Bala Hissar in 1933. The flavour is unmistakably modern: as well as the ancient fortress we can see motor cars and telegraph or telephone wires.

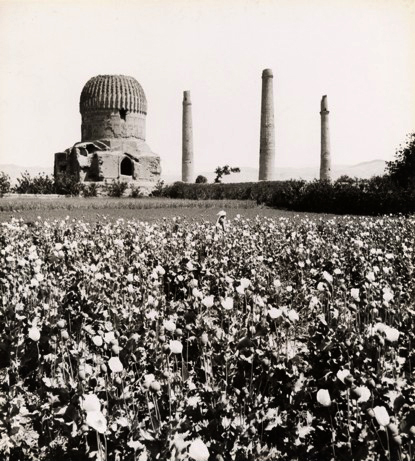

There is nothing military about the great travel writer and student of Islamic architecture, Robert Byron. His picture takes in the Mausoleum and three of the minarets at the Musalla in Herat. Originally there had been 30 minarets. All but nine were destroyed in 1885 on the advice of British army officers helping King Abdur Rahman defend Herat against the threat of a Russian invasion. Two others collapsed in an earthquake in 1931. So when Byron was in Herat seven minarets were still standing. These he described as the “most glorious productions of 15th Century Mohammedan architecture”. Today, after the Russian war, there are just five. In the foreground is a field of opium poppies. The date is May 1934.

Note: all photographs are copyright of the Royal Geographical Society. Their website is www.rgs.org; their picture library website is www.images.rgs.org; and their education website is www.unlockingthearchives.rgs.org.

Like us on Facebook

Like us on Facebook

Share this story